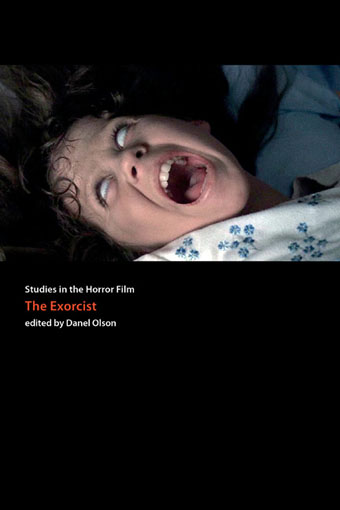

The Exorcist: Studies in the Horror Film (2011), edited by Danel Olson, Centipede Press: Colorado

The Exorcist: Studies in the Horror Film (2011), edited by Danel Olson, Centipede Press: Colorado

Reviewed by Robert Hood

In the general category of Good Horror Films, there are those that gain their status by the sheer exuberance of their handling of the tropes. These bring an illicit joie de vivre to the freakish monstrosity, darkness and unnatural threat, entertaining viewers with a special frisson that creeps us out, horrifies us, excites us and comforts us all at the same time. Such films are characterised as Lots of Fun.

Then there’s horror films like The Exorcist. Sure, as we learn in Danel Olson’s new and extremely comprehensive book on William Friedkin’s award-winning and influential movie, the director didn’t consider it to be a horror film at all — but reading what he does consider to be Horror, it’s easy to conclude that this denial is based on one of those idiosyncratic and limited definitions of the genre that all too commonly lie behind comments made about it even by practitioners. For me, as a horror writer and long-term fan of horror cinema, The Exorcist ticks all my boxes for not only being of the Horror genre but also for being up the top of its class. This is the real deal and I love it for that.

But how exactly does it differ from the first category I mentioned above? It certainly has a high creep-out factor. It horrifies with the best of them. It’s rather less exciting, in thriller terms, than many of its ilk, but it excites in other more profound ways. It doesn’t offer a lot of comfort, even though in the end it is an heroic, and redemptive, sacrifice on the part of the main character that saves Innocence, and such sacrifice tends to leave us, if briefly, feeling a little better about the fate of humanity. On the whole, however, The Exorcist is a difficult film to describe as “lots of fun”. In fact, watching it can be an emotionally grueling experience.

Let me tell you an anecdote. In 1973 when the film was showing in Sydney, the cousin of a close friend of mine went along to see what all the buzz was about. He came from a strong religious background and was reportedly a member of the ultra-conservative Opus Dei movement within the Catholic Church — an order given some considerable negative criticism in recent times for its alleged extremist tendencies as depicted in Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code and the 2006 film version of it. This particular viewer’s experience of seeing The Exorcist certainly proved to be a traumatic one. Reacting to the horrific manifestations of Pazuzu that the film depicts, he suffered some sort of fit during the main exorcism scene (or thereabouts) and fainted in shock, requiring cinema staff to help him from the auditorium so he could receive medical assistance. It’s hard not to see the influence of deep-seated conviction, expressed via the film’s powerful imagery, in this reaction. To his mind, the film’s reality couldn’t be interpreted as mere entertainment.

For me, however, it’s not the accuracy or assumed reality of its central subject matter that makes it a great horror film. What puts The Exorcist in the upper echelons of the genre is the emotional and thematic depth of it and the artistry that went into its creation. This is not some throw-away entertainment, but unequivocally a “serious” work of cinematic fiction — multi-layered, dramatic, character-driven and metaphorically powerful. There’s little wonder that it earned a reputation as the first horror movie to gain a Best Film Oscar nomination. Combined with its ongoing influence, it can be considered not just a “Cult Classic” but a genuine Classic.

In many ways The Exorcist transcends ordinary Horror films, thanks to its depth, resonance and proficiency as a cinematic experience — though I would argue that such transcendence is what all ambitious horror fiction should strive for. One doesn’t have to be a Catholic or even a Believer to buy into The Exorcist any more than one has to be a Royalist and an Elizabethan refugee to appreciate the artistry and emotional power of King Lear. The religious trappings of The Exorcist are important, as all details within good works of fiction are important, but at the heart of the experience they offer a metaphor that allows us to explore fundamental issues relating to life and its meaning. Like all great art, it is more than the sum of its parts and more than a depiction of surface realities.

The details, emotional depth, social context and thematic meanings that make The Exorcist the great work it is are what Olson’s book, The Exorcist: Studies in the Horror Film, explores. Film journalist David Bartholomew opens proceedings with a comprehensive history following The Exorcist‘s development from book to screen, outlining its production, opening and reception by both critics and general public, in an article reprinted from a 1974 edition of Cinefantastique. Interviews with the author of the novel (William Peter Blatty), the film’s director (William Friedkin), the man who starred as Father Karras (Jason Miller), Make-up artist Dick Smith and the film’s Editor Bud Smith, subsequently allow the reader to delve into the various aspirations and influences that drove the creative process and provide wonderful grass-root insight into its making.

In many ways, that’s all groundwork. Analysis follows from it, though of course hindsight interpretation of such a film is inevitably going to have a variety of foci. Articles by literary and film critics compare The Exorcist to other films of the period — in particular Don’t Look Now and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre — and examine its approach to metaphysical realities and themes of apocalyptic portent, sexual abjection, the breakdown of the family and the impact of generational conflict, redemption through sacrificial love, the value of human life, and more. Several articles examine the relative merits of the theatrical version and the latter-day “restorations”. The book then goes on to cast light on the disappointing The Exorcist 2: The Heretic, the creepily effective The Exorcist 3: Legion, and even the recent prequels — both of them. An interview with director Paul Schrader, who in a unique situation got to release his original version of Exorcist IV: Prequel (now known as Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist) after it had been pulled by the studio and re-filmed by Renny Harlin as a blockbuster-style flop) is fascinating and would surely put anyone off film directing if they hadn’t already lost their soul to the Demon of Cinema.

Keep in mind that The Exorcist: Studies in the Horror Film is not an academic tome as such, one with a coherent argument to make. Indeed it suffers somewhat from a patchy tonal landscape and lack of a conceptual “storyline” — inevitable given the archival nature of the content. But it contains an abundance of worthy material, all collected here in one place for your convenience, and is fascinating to read. It should be seen for what it is — a compendium of entertaining pop-culture analysis and a reference point for further discussion, beautifully illustrated with excellent colour images of Linda Blair in extremis.

In short, Olson’s lovingly assembled book is an excellent resource for anyone interested in The Exorcist, either as fan or cinephile. Indeed for the former, I would say it is an essential acquisition. You will need to have this book at hand the next time you sit down to watch the film.

And if nothing else, it illustrates how powerfully relevant Friedkin’s film continues to be.

The Exorcist: Studies in the Horror Film, edited by Danel Olson

Published by Centipede Press

ISBN 978-I-933618-96-8

Full cover, Smyth-sewn, 500+ page PPB.

Published by Centipede Press